I. Build idioms. Then tell about the hardest day in the last year of your life using at least 3 of them.

- Pardon my , but that's a damned shame!

- This contract is written in such complicated language that it’s all to me.

- You'll be in with your teacher if you don't hand in this assignment on time.

- Well, don't that beat the ! It's amazing what phones can do these days.

- The official story is that he's sick, but I think he's just taking leave.

- I know it's September, but don't get out your winter clothes just yet—this area often has an summer.

- The firm's CEO denounced the rumors of impending layoffs as being nothing more than whispers.

- Why are you home so early? Well, they made me walk .

- The students lined up and walked file into the auditorium.

- John is always lecturing me like a uncle, forgetting that I'm 40 years old!

Total Questions: 0

Incorrect Answers: 0

II Read the text and answer questions on it:

The English Reformation, unfolding (prime) between 1534 and 1559, was a turning point when religion and power collided with (last) consequences. When Henry VIII severed England’s ties with Rome through the Act of Supremacy, the change was political in origin but deeply social in effect. For ordinary (parish), the shift from papal to royal authority (feel) abrupt and confusing, as long-familiar religious customs were (rewrite) almost (night). New laws made loyalty to the Crown a religious obligation, and resistance could prove fatal—as demonstrated by the (execute) of Thomas More in 1535. The (dissolve) of monasteries soon followed, (distribute) church lands while removing institutions that had provided charity, education, and community support. Parishioners not only lost (spirit) traditions but also social safety nets.

Under Edward VI, Protestant reforms accelerated. Worship was (simple), services moved into English, and texts such as the Book of Common Prayer (shape) everyday religious life. Ordinary believers gained greater access to Scripture, increasing (literate) and encouraging personal interpretation of faith. At the same time, the authority of priests (weak), and religion became less ritual-centered and more focused on moral discipline, self-control, and work ethic.

This progress (reverse) under Mary I, whose restoration of Catholicism led to persecution, fear, and exile for many Protestants. Communities experienced instability, rumor, and renewed (anxious) as religious identity once again became a matter of survival. When Elizabeth I took the throne, her religious settlement enforced outward (conform) while (attempt) to (stable) the nation. Parishioners (expect) to follow a moderate Anglican path, (blend) tradition with reform. For many, the long-term effects included greater access to education, Bible reading, and individual (responsible) in matters of (believe); for others, the period meant cultural loss, (linger) division, and (trust).

In retrospect, the English Reformation reshaped parishioners’ daily (live) by changing how they worshipped, learned, worked, obeyed authority, and understood personal faith. It remains both a political triumph and a moral tragedy—an upheaval whose social and cultural echoes continue (feel).

Total Questions: 0

Incorrect Answers: 0

III. Answer the questions on the text:

-

Which years frame the main period of the English Reformation in the text?

Show answer (admin) -

What decisive 1534 measure severed England’s allegiance to Rome, and who enacted it?

Show answer (admin) -

Which high-profile execution illustrated that dissenters were “in Dutch” with the Crown, and in what year did it occur?

Show answer (admin) -

What happened to the monasteries in the late 1530s, and what was a major social or economic consequence?

Show answer (admin) -

Why is Edward VI’s reign (1547–1553) described as an “Indian summer” for reformers, and what key liturgical change marked it?

Show answer (admin) -

How did Mary I’s accession (1553) alter the religious course, and which phrase in the text captures the climate of rumor and fear?

Show answer (admin) -

What did Elizabeth I’s 1559 settlement require of subjects, and how does the text characterize her governance style?

Show answer (admin)

IV. To differentiate among the three Christian religions in Great Britain, do this matching exercise

Text A. Rooted in Western Christianity under papal authority, this religion treats Scripture and Tradition as co-authoritative and recognizes seven sacraments (baptism, Eucharist, confirmation, marriage, holy orders, penance, anointing of the sick). It affirms transubstantiation in the Eucharist and maintains a hierarchical structure led by the Pope and bishops. Before the Reformation in England, its institutions—parishes, monasteries, pilgrimages—shaped daily religious life and social welfare.

Text B. Emerging from the sixteenth-century reforms of Luther, Zwingli, and Calvin, this religion places final authority in Scripture alone (sola scriptura) and teaches salvation by faith alone (sola fide). Most traditions retain two sacraments (baptism and the Lord’s Supper) and reject transubstantiation—some hold a spiritual or “real” presence, others a symbolic view. Worship centers on preaching and Bible reading in the vernacular, and church governance varies (episcopal, presbyterian, congregational) across denominations.

Text C. Established in England by the 1534 Act of Supremacy, this religion made the monarch—not the Pope—the Supreme Governor of the national church. Shaped further by the 1559 Elizabethan Settlement and the Book of Common Prayer, it presents a via media (middle way): Protestant doctrine and Scripture in English combined with Catholic-style liturgy, cathedrals, vestments, and an episcopal structure with bishops. This compromise sought religious uniformity while accommodating a range of private convictions.

V. [Высшая проба] In the name of an ordinary parishioner tell about the influence of the Reformation on your life (approximately 250 words +- 10%)

You must include in your story:

-

an introduction,

-

a body of paragraphs and

-

a conclusion.

Make sure you mention:

a. what your life was like before the event,

b. what it was during the event ( revolution and confiscation),

c. what it was after the event.

You must also demonstrate the knowledge of the principles of storywriting in the HIGHER PROBE olympiad:

a. description of characters' appearance, character,

b. direct speech

To make sure your syntax in direct speech in your story is correct, watch my video about it. And give your thumbs-up👍):

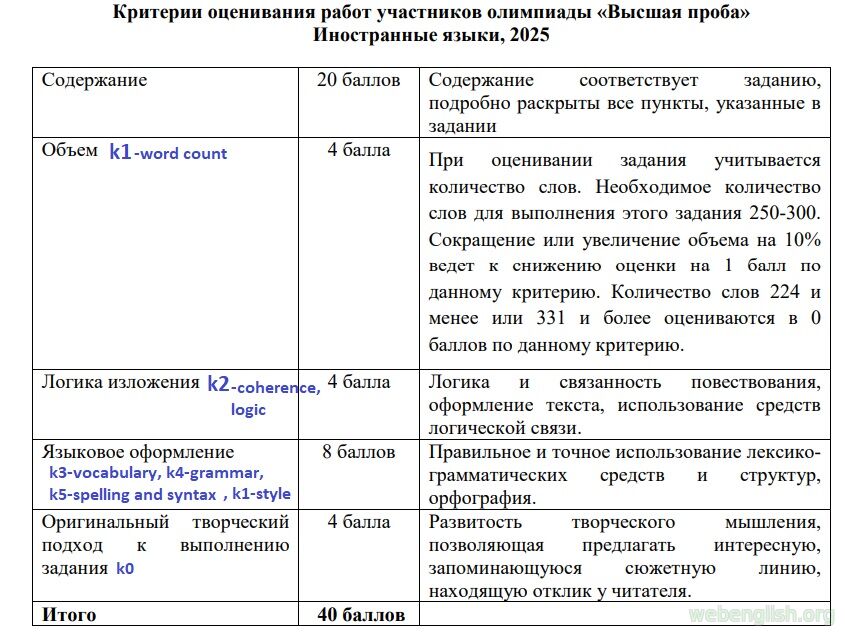

Assessment and Scoring criteria in Higher Probe